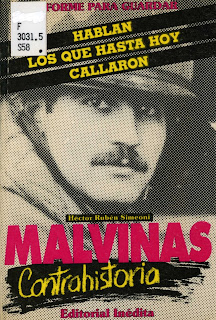

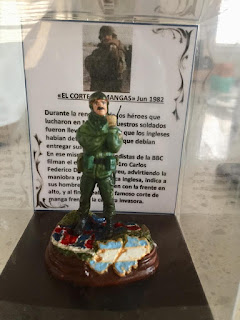

El Corte de Manga - Guerra de las Malvinas/Falklands War

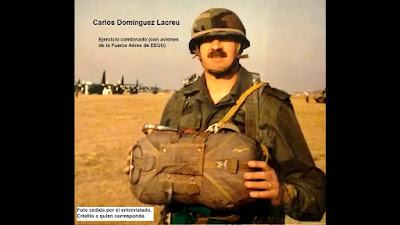

I was the commander of Company A, Regiment 25, which occupied the entire length of the airport runway. We didn’t fight — we endured. The constant shelling from the naval guns, the relentless bombardments. I don’t even know which was worse. We were also subjected to the psychological pressure of delayed-action bombs.

That’s how they worked: the plane would fly over, drop two or three bombs — one would explode right away, and the others would land and stay buried, waiting hours before going off. The danger was always there, constant. Those bombs dug themselves into the ground, and finding them was almost impossible.

All we could do was hang on and keep preparing ourselves. Until the British landed at San Carlos, we believed the main assault would come at the airport — the only area with wide, open beaches suitable for a large landing. The regimental commander prepared us mentally for that eventual attack.

But it never came.

I had never imagined the Falklands War would be like this. Not at all. I thought I’d be up front — like Regiments 7, 4, and 3 — that I’d be able to fight. I never imagined I’d end up where I did, in what would later become the rear guard.

It was a hard day. Still, there were moments of humor — brief, unexpected flashes in the middle of all that tension. Unfortunately, I could hardly enjoy them. The responsibility of leading a company leaves little room for laughter. I had 148 men under my command — and above me, in that sector, no one. It’s true the regimental commander supervised everything and came by every day, but he was at his own post.

I felt what, in military terms, is called the loneliness of command. The company commander is the one man who cannot afford to joke, to relax, to fool around. Still, I could see the good humor in my men — and that gave me strength.

I’ll never forget May 1st. Around four in the afternoon, the frigates started bombarding us with everything they had. But then our Mirages appeared, and they dove straight at them. My men jumped out of their trenches, cheering, waving their arms — celebrating the attack as if they were at a soccer match. Fear and joy, all mixed together.

A company commander feels toward his men the same way a father feels toward his household: other people’s fates depend as much on his successes as on any mistakes he might make. He trembles, like the head of a family, at the thought of a son dying. Thank God none of ours did — I only had wounds.

We dug our positions until our hands bled. From the commander who had no problem grabbing pick and shovel, down to the last private — everyone dug his own hole. The lieutenant colonel supervised it all closely. Every day I walked the works and checked the fortifications. While most people thought the British wouldn’t come, he knew a fight was coming and prepared us to meet them.

My soldiers were outstanding. I remember one moment that says it all. There’s a bomb designed specifically to ruin airstrips — it has its fuze in the rear, not the nose. When it hits, it bores into the ground roughly six meters and then blows up, opening a crater six meters across in the rock or concrete.

At five in the morning on May 4, a string of those bombs fell across our company sector. A high-altitude “Vulcan” seemed set on taking the runway away from us for good. We were spread out every forty meters along the strip. But that pilot missed the runway — his bombs hit right on our positions. When it finally quieted down I asked my section leaders for reports; they passed the word along to their groups and answered with the same terse, comforting phrase: “No news.” But it wasn’t true. In the second section two men were missing.

So we went after them. If the bomb had destroyed them we’d have to gather the pieces, wrap them in a blanket, load them on a truck — anything to spare their comrades the shock of finding a limb by the position at dawn. I ordered the search teams to bring me a report before first light. I didn’t want anyone stumbling on remains in the morning.

They called me after a while to say: the two had been found — stunned, covered in dust and bleeding, but alive. They’d been blown clear of the crater and buried under rubble, but they were alive. They were bruised to the soul, shaken and furious, but they were there. We took them to the regimental doctor; he checked them over and sent them to the hospital to be looked after.

When we pulled them out, they were deaf, dazed, furious, and scared shitless — poor guys. But alive. Of course, they were bruised all over, even in the soul. The regimental doctor came, checked that they had no stab or gunshot wounds, and sent them off to the hospital to be properly cared for.

I was genuinely surprised when, four days later, the two of them showed up at the company, proud as could be, and said to me:

“We’re fine, sir. We’re going back to the regiment.”

They were just soldiers — two months of training, no more.

Throughout the whole war, we were practically never moved from the airport. Not even a repositioning, no reorganization of the defensive line. We suffered the strain of being stuck, inactive, in position for weeks. Only on the night of June 13 to 14 were two of my sections sent out to try to block the British advance west of Moody Brook — which by that point was unstoppable. But when they got there, they found that the units they were supposed to support had already pulled back.

Then came June 14. The order reached us: it’s over. No more fighting. Lieutenant Colonel Seineldín had wanted to cut all communication with Puerto Argentino and make a stand at the airport — to resist, not surrender. Our position was separated from the town by an isthmus.

If the situation becomes untenable, the higher costs destroy you. We were overwhelmed by the enemy’s training and by our own stagnation.

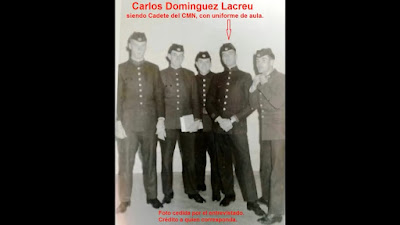

When the question came up — should we keep fighting to the last man instead of surrendering? — there were two answers: the one I gave as Domínguez Lacreu, and the one the First Lieutenant Domínguez Lacreu gave.

I thought we should have held out until there was only one man left — that last soldier, flag in one hand and bayonet in the other, would go down fighting, every one of us. The First Lieutenant, though, answered more practically: if our people had had years of training like those who attacked us, if they’d been kept in fighting condition, with weapons that worked and bodies fit for the job, then maybe. But that wasn’t our reality. In any case, on the 15th Seineldín ordered us to turn in our weapons — because they were going to retaliate against the prisoners taken up front.

So we unloaded the rifles, removed the slides, the pistons and other parts. We threw everything into the sea.

What really bothered me was how the previous day’s handover had been done. Some men had gone up looking broken, defeated, miserable. So I formed my company out on the runway, gathered the section commanders, and gave them one last order: when we went to the ramp to leave the weapons, we would not present ourselves as defeated.

I gave them a harangue, telling them they would march with their heads held high, at double time, as soldiers should. That even though we had been ordered to hand over our weapons, we should not consider ourselves defeated — because we had not been taken. When I finished speaking to my men, I sent them to their officers to take charge of their sections and gave the order to dismiss.

The airport had been turned into a kind of concentration camp. The British guards kept a tight watch on us — they still didn’t know that our weapons were no longer in any condition to fire. While I was addressing my soldiers, some of the British guards and a group of their journalists had come up behind me. I didn’t notice them until I gave the order to break ranks. When I turned around and saw them there, listening, it made my blood boil.

I walked off, furious, and the only thing that came to me in that moment was to turn around, face all their photographers and cameras, and shout:

“¡Me los meto en el culo, por ustedes!” — or, as I said in English:

“I’ll shove them up my ass—for you!”

And I gave them the corte de manga — the gesture. I never imagined they’d actually leave it in the film.

What came after hardly matters. The British soldiers grabbed me and kicked me around a bit. But it didn’t go any further — my men reacted right away. Two or three of the nearest ones stepped forward, ready to fight. And since the British still weren’t sure whether our weapons worked or not, they backed off rather than start another battle.

I didn’t think much of it and just kept walking. They were the ones who stayed angry. I never imagined they’d be clever enough to stick my scene into one of their films. They even put in an Argentine who tells them all to go to hell. I swear, I did it with every intention of screwing them over — of wrecking their take, of ruining their film.

Later on, I found out what they’d done. But I only saw that movie last year, when I came back to take a course for the War College. They screened it at the Military Circle. When my wife saw it, she just said, “What a crude piece of work.”

Anyone who’d felt the frustration, the rage, the helplessness we went through would have done the same — to mess with them somehow. But even when we were at a disadvantage, we weren’t cowards like they were. They never fought us head-on. They only moved when the shooting stopped, always striking from the shadows. They only dared attack when they’d hammered us with artillery and knew they had the upper hand.

Take Major Castagnetó’s commando patrol, for example — they gave the Brits their first real scare. The English dropped their packs, weapons, radios, keys, everything — and ran.

At first light, the fishermen set out once again. This time it was Loguzzo and Chilavert who undertook the long swim. Drawing on experience, they took a precaution: after anchoring, they rigged a brightly colored awning on the boat. In addition to shielding the man who remained aboard from the sun, it allowed those returning from shore to identify the vessel from a distance. A fairly compact group waited on the beach for the return of these Argentines, avid fishermen who sold the catch from their expeditions at very reasonable prices.

To further enhance their popularity, Loguzzo grilled a generous quantity of fish on the shoreline at midday. He and his companions ate, offering appetizing portions to those nearby. After lunch, as the town observed the customary midday siesta, the three men made their way to the quarters of the Support Group.

At 4:40 a.m. on May 12, the first bomb detonated in Puerto Argentino. Fifteen more followed in rapid succession. Moments later, the roar of an RAF bomber’s engines faded into the night. The second round of the Battle for the Malvinas had begun.

The mission assigned to Flight Lieutenant Martin Withers, commander of the bomber—a Vulcan B.2, tail number XM-607—was, at the time, the longest-range bombing mission ever conducted. The operation, designated Black Buck 7, involved thirteen aircraft and required seventeen aerial refuelings. It also produced several incidents related to rendezvous and coupling with Victor tanker aircraft. Despite the magnitude of the effort, the results did not justify the undertaking.

Of the twenty-one bombs released by the Vulcan, only one struck the southern edge of the runway at Puerto Argentino. Even that hit failed to impair operations, as the runway remained fully serviceable throughout the conflict, despite being the principal objective of British air attacks.

Following the strike, Argentine forces devised a deception that the British were slow to detect: they painted several simulated craters on the runway, which—had they been real—would have rendered it unusable.

Aside from the single direct hit, the remaining bombs dropped by Withers fell harmlessly into the peat. Two detonated after a delay, fitted with fuzes designed to postpone their explosion, while four failed to detonate altogether.

As a result of this first enemy air raid, First Lieutenant Domínguez Lacreu quit smoking.

The Vulcan had already departed when a message arrived via the field telephone: two soldiers were unaccounted for.

“Search for them,” the officer ordered. “At the very least, we owe their families the recovery of the bodies.”

Moments later, the field telephone rang again.

“We can hear groaning underground, my First Lieutenant,” came the report.

“I’m on my way.”

As he moved toward the site in the darkness before dawn, Domínguez Lacreu vowed to the Virgin that he would stop smoking if the two soldiers were found alive.

One of the Vulcan’s bombs—designed to fragment reinforced concrete—had created a crater approximately sixteen meters in diameter and eight meters deep. Beneath the lip formed by the displaced earth at the edge of the crater, muffled cries could indeed be heard.

The men dug frantically and eventually pulled both soldiers from the churned peat. They were badly bruised but otherwise unharmed. The short brims of their helmets and their balaclavas, pulled up to their eyes, had formed small air pockets that allowed them to breathe until rescue, when they were already close to asphyxiation.

First Lieutenant Domínguez Lacreu kept his promise.

Poema a Carlos Federico Dominguez Lacreu (Malvinas)

CELEBRACION Y ELOGIO

PARA UN CORTE DE MANGA

Te ví en una película llegada de inglaterra

con la versión británica respecto a nuetra guerra.

No importa la película pués haré referencia

de su extención tan sólo a una breve secuencia.

El gral. menéndez, la historia ha de juzgarlo,

ya resignó su sable sin llegar a empuñarlo,

bajo cielo plomizo bajo custodia armada

avanza una columna para ser embarcada.

Marchan nuestros soldados arrastrando las botas,

envueltos en sus mantas y masticando derrotas,

y marchabas con ellos en el extremo izquierdo,

de una fila marchabas según lo que recuerdo.

Caminabas a largas zancadas desparejas

y llevabas el casco metido hasta las cejas;

los dientes apretados el ceño de tormenta,

tu bigote era hoguera despeinada y violenta.

Bigotes colorados de bárbaro insepulto;

bigotasos propicios al alcohol y al insulto.

Caminabas con largas zancadas insolentes;

las cámaras siguieron tus pasos con sus lentes.

Caminabas ajeno a tales circunstancias,

la mirada sombría perdida en las distancias.

Al frente la mirada y en los tímpanos ecos

de cien mil estampidos repetidos y secos.

Sin embargo, de pronto, después de haber pasado

delante de las cámaras feroz ensimismado,

reparaste en el rol, el rol involuntario

que protagonizabas para el bando adversario.

Desandaste lo andado y altivo, compadrón

te plantaste delante de la televisión.

Registró el celuloide tu estampa socarrona,

con los brazos en jarras, la sonrisa burlona.

Tus bigotes de lacre a la sombra del casco,

dibujan un visaje de humor, de bronca, de asco.

Entonces, lentamente, cincelaste en un gesto

la actitud inequívoca de quién conserva resto.

Fue el tuyo un admirable corte de manga clásico,

planetario, doméstico, académico y básico.

Fue un gran corte de manga, armonioso directo,

superlativo homérico, delicioso, perfecto,

sublime, cosmogónico, excelso, escatológico,

musical, metafísico, ejemplar, pedagógico.

Te agradezco soldado tu arrebato atrevido,

aunque ignore tu nombre e ignore tu apellido.

Ni siquiera llevabas distintivo ninguno,

anónimo guerrero del sarcasmo oportuno.

Agradezco tu gesto repentino y audaz;

agradezco tu gesto patriótico y procaz.

Simbólico exabrupto, dirigido tal vez

no solo al enemigo, al vencedor inglés,

sino a la cobardía de aquel jefe prudente

que jamás ocupó su lugar en el frente;

al superior cobarde y al gobernante inepto;

al cálculo fallido y al errado concepto;

al cauto periodista que retaceó su aliento

al especulador que aprovechó el momento;

Al político dúplice, al literarto críptico,

Al abogado cómplice, al ideólogo elíptico,

Al funcionario escéptico, al mendaz catedrático

Al ámbito soviético y al mundo democrático.

Al este y al oeste, al imperio británico,

Las Naciones Unidas y su Estatuto Orgánico,

A la Comunidad mercantil europea,

A cada voto adverso emitido en la OEA,

Al modo como actuaron los norteamericanos,

A las Ligas que agitan los derechos humanos,

Celebro , combatiente, tu gesto simple y gráfico,

Tu rotundo ademán docente y pornográfico.

Tu gesto dirigido hacia todos los vientos,

Que involucra no obstante opuestos sentimientos,

Pues implica un arranque de gratitud primaria,

que puede establecerse por deducción contraria.

Tu repudio, en efecto, tambien es expreción

de apoyo para quienes te dieron su adhesión.

Expresión paradójica de afecto transitivo

Abrazo recato, tangencial, primitivo.

Escueta acción de gracia al pueblo solidario

Y al generoso impulso de cada voluntario,

y a cada escarapela que adornó una solapa,

y a cada plaza llena que animó nuestro mapa.

Al aporte entregado en la colecta pública,

A la emoción patriótica de toda la República,

A los tantos rosarios desgranados en coro,

Pidiendo la victoria o una paz con decoro,

A la voz espontánea, diferente y genérica,

de apoyo que elevaron las naciones de América,

al piloto esforzado y al marino cabal,

al conscripto, al gendarme, al cabo, al oficial,

que suplieron cumplir con su deber de soldados

en aquellos lejanos parajes desolados,

al jovial camarada que segó la metralla,

a la sangre fraterna derramada en batalla.

Por éstas y otras cosas que tu gesto delata,

lo celebro guerrero del bigote escarlata.

Celebro tu ademán, celebro tu talante,

celebro el alegato inscripto en tu desplante.

Y propongo que el bronce conserve en alegórico

monumento tu gesto canyengue y metafórico.

Tu brazo proyectado en trunca trayectoria

nos estará indicando el rumbo de la Historia.

Con su órbita inconclusa, tu antebrazo ascendente

dirá de la existencia de un asunto pendiente.

Plástico y elocuente tu ademán detenido

gritará que la guerra no es asunto concluído.

Pués allí, circundadas por espuma revuelta,

LAS MALVINAS esperan, esperan nuestra vuelta.

Y tu corte de manga nos señalará el camino

Que nos lleve otra vez hasta PUERTO ARGENTINO.

FIN.

Autor: Juan Luis Gallardo